Understanding the layout: Citadel, Imperial City & Forbidden Purple City

When researching Hue’s historical sites, you’ll likely come across the terms Hue Imperial City, Hue Citadel, and Forbidden Purple City. While they are often used interchangeably, they each refer to different parts of the same royal complex — and understanding the layout will help you make sense of what you’re visiting.

- The Hue Imperial City is the central section of the larger Hue Citadel, and it served as the administrative and ceremonial center of the Nguyen Dynasty. It’s where you’ll find major attractions such as the Thai Hoa Palace, royal temples, and the emperor’s working quarters.

- Surrounding the Imperial City is the Hue Citadel, a massive fortified enclosure with thick defensive walls and gates built to protect the imperial capital. It was designed with military strategy in mind, modeled after Chinese citadel designs.

- At the very heart of the Imperial City lies the Forbidden Purple City, an exclusive residential zone where only the emperor, his family, and select attendants were allowed. It was the most private and restricted part of the imperial compound.

For a full overview of the citadel’s defensive structures, visit our guide to the Hue Citadel. To explore the emperor’s private residence in more detail, check out our article on the Forbidden Purple City.

History of Hue Imperial City

The birth of a royal capital

The Hue Imperial City was established in the early 19th century by Emperor Gia Long, the founding ruler of the Nguyen Dynasty, which became Vietnam’s last imperial dynasty. After unifying the country in 1802, Gia Long moved the capital to Hue and began building a grand imperial complex to serve as the political, cultural, and ceremonial heart of the nation. Construction of the Imperial City began in 1804, following a design inspired by both Chinese imperial palaces and Vietnamese geomancy (feng shui).

Located at the center of the larger Hue Citadel, the Imperial City was enclosed by a second set of walls and gates and carefully aligned along a north–south axis, with mountains behind and the Perfume River flowing in front. It was designed as a city within a city — the seat of royal power, and the stage for official ceremonies, ancestor worship, education, and state governance.

Layout and daily life within the walls

The Hue Imperial City was organized into different zones, each with a specific purpose. At the front were the main gates and reception halls for official guests and public ceremonies. At the center stood the Thai Hoa Palace, where the emperor held court and met with mandarins. Deeper inside were the residences of the royal family, temples, libraries, and administrative buildings. Behind all of this, protected by a third layer of walls, lay the Forbidden Purple City — the emperor’s private domain, restricted even to most members of the court.

Life inside the Imperial City was highly structured and deeply symbolic. Architecture reflected strict Confucian hierarchy, and every detail — from the layout of doors to the placement of shrines — was designed to project imperial authority and harmony. The city housed thousands of court officials, guards, servants, concubines, and of course, the royal family itself. It was not just the emperor’s residence, but the center of Vietnamese imperial culture for over a century.

Imperial decline and wartime destruction

The Nguyen Dynasty ruled from Hue for 143 years, from 1802 until 1945, when Emperor Bao Dai abdicated in favor of the new communist government in Hanoi. After that, the Imperial City was no longer in use, and its decline began. The real devastation, however, came during the Vietnam War.

In 1968, during the Tet Offensive, Hue became the site of intense urban combat between North Vietnamese and South Vietnamese/US forces. Much of the Imperial City was caught in the crossfire. Bombs, artillery, and street fighting caused widespread destruction, and an estimated over 70% of the buildings inside the Imperial City were damaged or destroyed.

Preservation and restoration

Despite its wartime scars, the Hue Imperial City remains one of the most important cultural landmarks in Vietnam. In 1993, it was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and restoration efforts have been ongoing ever since. While many original structures were lost, key buildings like the Thai Hoa Palace, the Mieu Temple complex, and several gates and pavilions have been restored or rebuilt.

Today, walking through the Imperial City is like stepping into the pages of Vietnamese royal history. Though incomplete, it remains a powerful symbol of Vietnam’s dynastic past, cultural identity, and efforts to preserve its heritage for future generations.

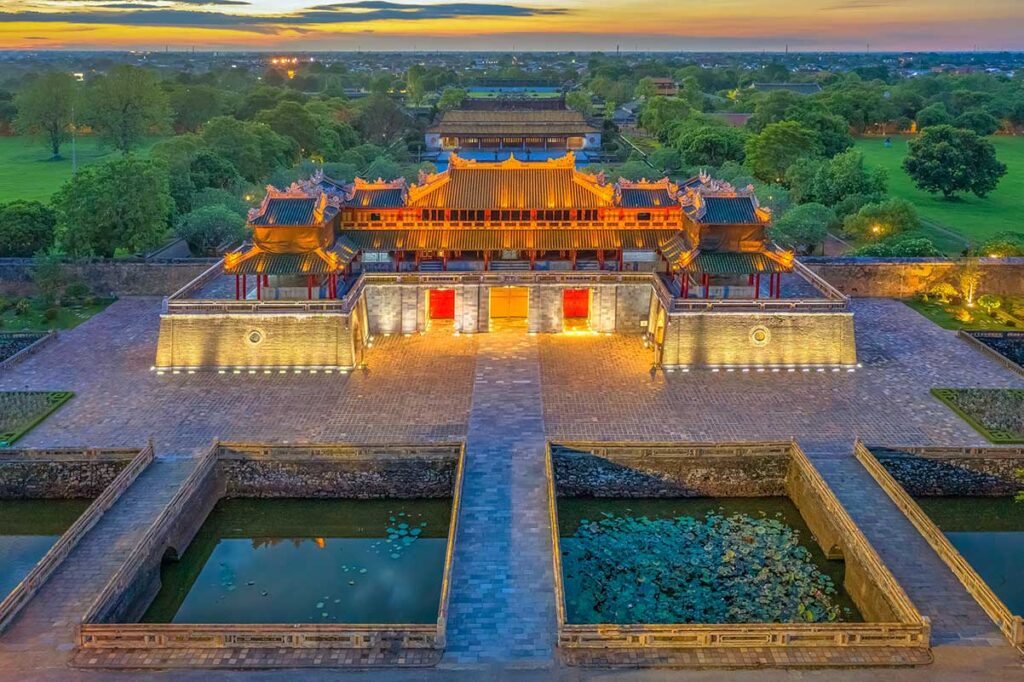

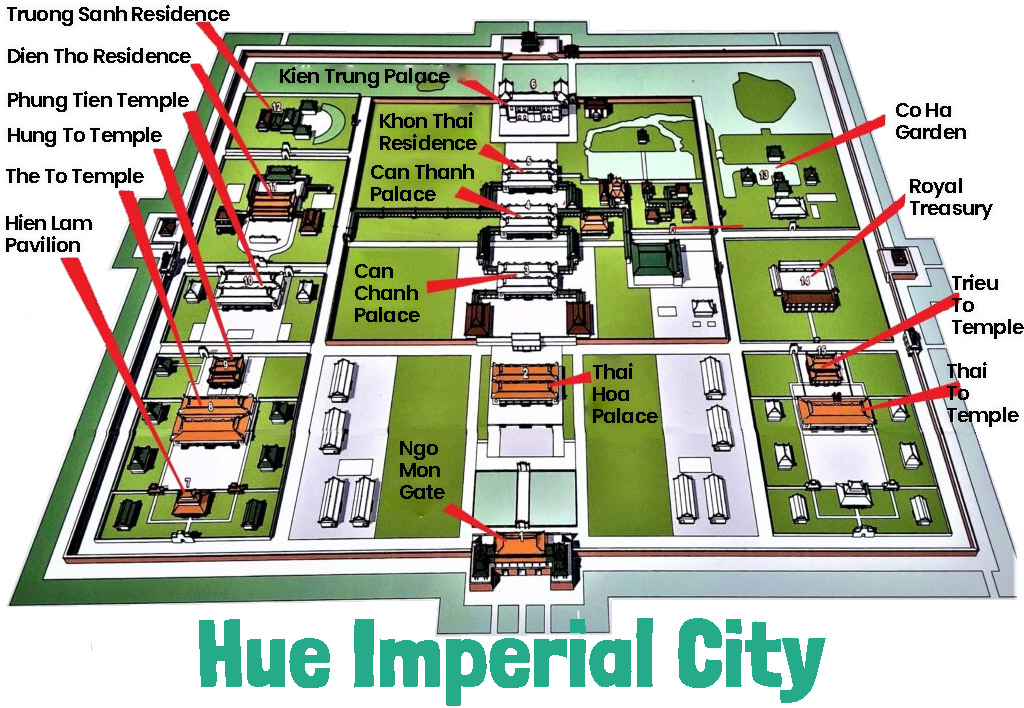

Map of Hue Imperial City

The Hue Imperial City is a large and complex site, so using a map helps make sense of its layout and highlights. Key landmarks are spread across different zones, and some restored buildings can be easy to miss without orientation. Below, we guide you through the main places to see on the map — and why they’re worth visiting.

Hue Imperial City Highlights & Things to see

The Hue Imperial City is full of fascinating remnants of Vietnam’s royal past — but not everything has survived. Many structures were heavily damaged or completely destroyed during the Vietnam War, and restoration is still ongoing. That’s why it helps to know which areas are most impressive and still accessible today.

Below is a carefully chosen list of the best-preserved, most significant, and most interesting places to see inside the Imperial City. These are the buildings and spaces that offer the clearest picture of imperial life, architecture, and ceremony — and they’re the parts you absolutely shouldn’t miss.

1. Ngo Mon Gate

The Ngo Mon Gate is the grand southern entrance to the Imperial City and one of its most iconic structures. Built in 1833 by Emperor Minh Mang, this massive U-shaped gate served not just as an entryway, but as a ceremonial stage for royal proclamations and military parades. It stands directly opposite the Flag Tower and faces the main axis of the complex, perfectly aligned with the Thai Hoa Palace behind it.

Architecturally, the gate is built from large stone blocks and features five separate entrances — but only the central archway was reserved for the emperor. The side gates were designated for mandarins, military officials, and servants, based strictly on rank. On top of the gate is the Lầu Ngũ Phụng, or “Pavilion of Five Phoenixes,” a beautifully crafted wooden structure used by the emperor to review troops and oversee important state ceremonies.

2. Dai Trieu Nghi (Great Ceremony Courtyard)

After passing through Ngo Mon Gate, visitors step into the Dai Trieu Nghi, or Great Ceremony Courtyard — a vast open square where the emperor once held court and received high-ranking officials from across the kingdom. This large, stone-paved space was more than just a plaza; it was the formal stage for imperial authority, where grand processions, royal proclamations, and foreign delegations took place.

The courtyard is divided by two slightly raised terraces: one side for civil mandarins, the other for military mandarins — a physical reflection of the Confucian hierarchy that governed the royal court. Standing here, it’s easy to imagine the rows of officials in bright ceremonial robes, lined up in strict formation to bow before the emperor.

3. Thai Hoa Palace

At the far end of the Great Ceremony Courtyard stands the Thai Hoa Palace, also known as the Palace of Supreme Harmony — the most important building in the entire complex. Completed in 1805, this was where emperors were crowned, celebrated their birthdays, and held the most formal court sessions. Only the highest-ranking officials were allowed inside during ceremonies.

The palace itself is a masterpiece of traditional Vietnamese imperial architecture. Its two-tiered yellow-tiled roof is supported by 80 intricately carved wooden columns, all painted red and decorated with golden dragons, the symbol of imperial power. Inside, the focal point is the imperial throne, set on a raised platform beneath a richly decorated canopy.

Despite damage over time, Thai Hoa Palace has been carefully restored and remains one of the most intact and visually striking buildings in the Imperial City. Its scale, symmetry, and symbolism make it an essential stop — and one of the clearest expressions of the Nguyen dynasty’s power and refinement.

4. Kien Trung Palace

Kien Trung Palace is one of the most impressive restored buildings in the Imperial City, newly reopened to visitors in 2024 after decades in ruins. Originally built between 1921 and 1923 by Emperor Khai Dinh, it served as the private residence of both Khai Dinh and his successor, Bao Dai — the last two emperors of the Nguyen dynasty.

The palace stands out for its fusion of Vietnamese imperial design with European influences, featuring ceramic mosaics, arched windows, and French-style decorative elements. Historically, it played a key role during the final years of the monarchy — most notably as the place where Emperor Bao Dai prepared for his abdication in 1945. Now fully reconstructed, it offers a rare look into the modern face of Vietnam’s royal legacy.

5. Dien Tho Residence

Tucked away in a quieter corner of the Imperial City lies the Dien Tho Residence, the private quarters of the Queen Mother. This complex of elegant wooden buildings, connected by covered walkways and set around peaceful gardens and ponds, is one of the best-preserved living spaces in Hue.

Originally built in the early 19th century and expanded under later emperors, the residence was not only the home of the emperor’s mother but also a retreat from the formal rigidity of court life. The layout reflects both respect and comfort: ceremonial halls in the front, and cozy, more intimate spaces for daily living tucked behind.

6. To Mieu Temple Complex

The To Mieu Temple Complex is one of the most sacred areas of the Imperial City, dedicated to the worship of the Nguyen emperors. Built in 1821 under Emperor Minh Mang, this sprawling compound was designed to honor past rulers through a series of shrines, altars, and ritual spaces. It was modeled after the ancestral temples of the Chinese emperors but adapted to Vietnamese aesthetics and beliefs.

The main hall houses ten ancestral altars, each dedicated to a different emperor. What’s especially fascinating is the way these altars reflect history: seven are ornately decorated for emperors who cooperated with French colonial rule, while three are more modest — added later to honor those who resisted foreign influence. The temple was restored in the late 1990s and today remains one of the most impressive and spiritually charged spaces inside the complex.

7. Nine Dynastic Urns

Just outside the To Mieu Temple stand the Nine Dynastic Urns (Cửu Đỉnh), cast in bronze between 1835 and 1837 under the reign of Emperor Minh Mang. These towering ceremonial urns — each over two meters tall and weighing around two tons — represent the nine emperors of the Nguyen dynasty up to that point.

Each urn is elaborately decorated with 17 symbolic engravings, showcasing everything from celestial bodies and landscapes to mythical creatures and native plants. The central urn, dedicated to Gia Long, the dynasty’s founder, is the largest and most intricate.

8. Hien Lam Pavilion

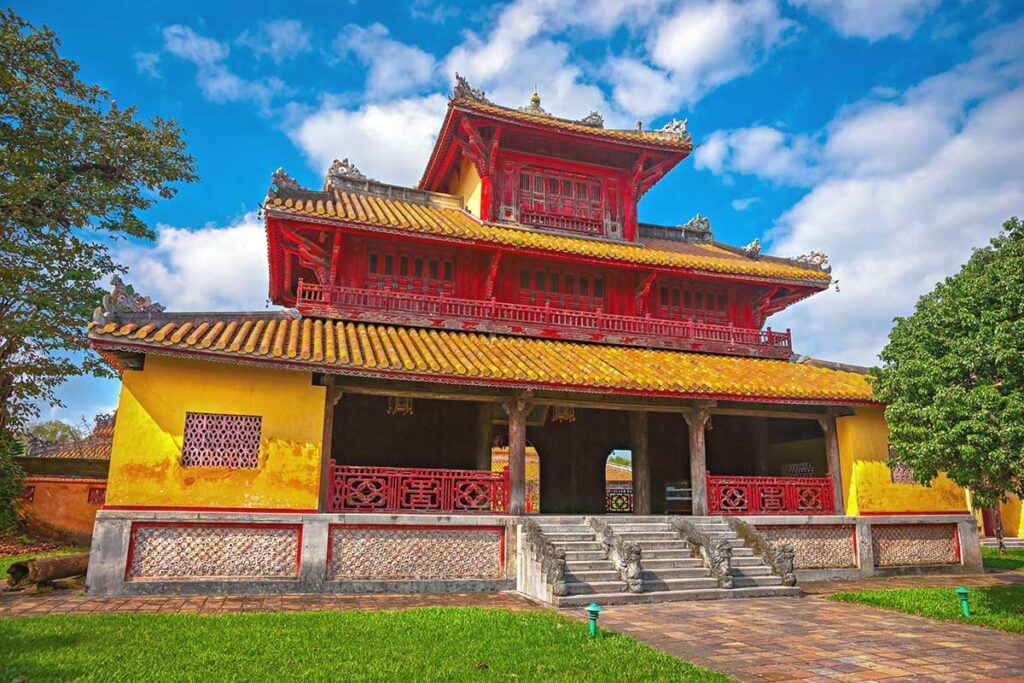

Standing just behind the Nine Dynastic Urns is the elegant Hien Lam Pavilion, a three-tiered wooden tower built in 1824 to honor those who contributed to the founding of the Nguyen dynasty. At the time of construction, a royal decree was issued forbidding the erection of any structure within the citadel higher than this pavilion — a symbolic gesture to ensure the moral and spiritual supremacy of those it commemorated.

The architecture is graceful but imposing, with layered roofs, carved railings, and a stately presence that anchors the temple courtyard. Climb its steps (if open to the public) and you’ll get a better view of the To Mieu complex and the symmetrical layout of this sacred zone.

9. Hung To Mieu Temple

Behind the main To Mieu temple lies the more modest but equally important Hung To Mieu Temple, built in 1804 by Emperor Gia Long. It was constructed to honor his parents, and it reflects the Confucian value of filial piety — a key principle in Vietnamese royal culture.

Though smaller than To Mieu, the temple has a quiet dignity, with clean lines and a respectful simplicity in its design. Like many structures in the Imperial City, it was damaged during war and restored later in the 20th century. Today, it stands as a reminder of how personal devotion and political legitimacy were closely linked in the Nguyen dynasty.

10. Royal Theatre (Duyet Thi Duong)

Tucked into a quieter corner of the Imperial City is the Royal Theatre, known as Duyet Thi Duong — the oldest surviving court theatre in Vietnam, built in 1826. This was where emperors and high-ranking officials were entertained with classical Vietnamese performances, including imperial music (Nhã nhạc), dance, and opera.

From the outside, it’s a refined wooden structure with sweeping tiled roofs and subtle ornamentation. Inside, visitors can see the stage setup, costumes, and sometimes even catch a live performance if visiting at the right time of day. The theatre continues to host short traditional shows — often three times daily — giving modern audiences a glimpse into the refined leisure culture of Vietnam’s imperial elite.

11. Thai Binh Reading Pavilion

Hidden behind trees and gardens, the Thai Binh Reading Pavilion is one of the most beautifully restored and peaceful spots in the Imperial City. Built in the early 20th century under Emperor Khai Dinh and expanded by Bao Dai, it served as a private space where emperors could read, write, and escape the formal pressures of court life.

The building itself is a gem — delicately constructed with intricate wood carvings, lacquered panels, and inlaid mother-of-pearl motifs. Set on a raised stone platform and surrounded by a lotus pond, the pavilion has an almost meditative stillness that makes it stand out from the more imposing structures nearby.

12. Forbidden Purple City

At the heart of the Hue Imperial City once stood the Forbidden Purple City, the most restricted and private area of the entire royal complex. Inspired by Beijing’s Forbidden City, it was built as the exclusive residence of the emperor, his concubines, and personal attendants. Even top mandarins could not enter without direct permission.

Sadly, this area was one of the most heavily damaged during the Vietnam War, especially during the Tet Offensive of 1968. Today, only a few structures remain, and most of the site consists of foundations, pathways, and explanatory signage. But despite its ruined state, walking through the grounds still evokes the secrecy and power that once defined this inner sanctum.

There are efforts underway to restore parts of the Forbidden Purple City, and the surviving gatehouses and walls give a sense of its former scale. For visitors with a bit of imagination, it remains one of the most intriguing and mysterious places inside the Imperial City.

Visiting information

Location

Thuan Hoa Ward, Hue, Vietnam — located right in the city center, just across the Perfume River from most hotel areas.

Opening times

- Summer (April to September): 8:00 AM – 5:30 PM

- Winter (October to March): 7:30 AM – 5:00 PM

Open daily, including weekends and holidays.

Entrance fee

- Adults: 200,000 VND

- Children (7–12 years): 40,000 VND

- Children under 6: Free

If you also plan to visit several of the royal tombs, it’s worth buying a combo ticket, which includes the Imperial City and multiple tombs — a good way to save money and skip extra lines.

Dress code

There is no enforced dress code, but it’s best to dress modestly out of respect. The Imperial City is a historic and culturally important site. Avoid wearing clothing that is too short or revealing, especially when visiting temples or royal altars.

How to get there

Hue is easily reached by domestic flights, long-distance buses, or the north–south railway line, with good connections to cities like Da Nang, Hanoi, and Ho Chi Minh City. Once in Hue, the Imperial City is centrally located — just across the Perfume River from the main hotel and restaurant area.

Walking

If your accommodation is near the river’s south bank, you can likely reach the Imperial City on foot in 15 to 25 minutes. The walk is pleasant — just follow the riverside promenade and cross one of the main bridges. Keep in mind, though, that the Imperial City itself involves a lot of walking, so if you want to conserve energy, another transport option might be better.

Taxi or Ride-Hailing Apps

For a quick and comfortable ride, use a Grab car or motorbike via the Grab app — the most convenient way to get around Hue. From most areas in the city center, the fare is usually under 2 USD. Even from further out, it rarely costs more than 4 USD. GrabBike (motorbike taxi) is also a fun and affordable local experience if you’re traveling solo.

Cyclo

Hue is known for its charming cyclo rides, and this traditional mode of transport fits the city’s calm, historic atmosphere. While cyclos are mainly used for short sightseeing circuits, you can also hire one for a direct trip to the Imperial City. Expect to pay up to 100,000 VND for a short ride, but you may need to negotiate the price in advance.

Guided tours

Many travelers choose to visit the Imperial City as part of a guided day tour, which often includes hotel pickup, transportation between sites, and insight from a local guide. Tours can be private or in small groups, and are frequently combined with visits to royal tombs, local markets like Dong Ba, or a dragon boat cruise on the Perfume River. A great option if you want historical context without navigating everything on your own.

Hue Historical City Tour

- Includes Hue Imperial City, royal tombs, temples, and a dragon boat ride on Perfume River.

- Options Small group or private tour with hotel pickup

Travel tips for Hue Imperial City

With a site as large and historic as the Hue Imperial City, a bit of preparation can make your visit much more enjoyable. These quick tips will help you plan your time, stay comfortable, and experience the best the site has to offer.

Best time to visit

The Imperial City is one of Hue’s top attractions and can get crowded, especially on weekends and during Vietnamese holidays. The best time to visit is early in the morning when it’s still quiet and not too hot. Late afternoon can also be peaceful, but keep in mind that the site closes relatively early, and you may not have enough time to explore everything.

How long to plan for the visit

If you’re just hitting the main highlights, two hours may be enough. But if you want to take your time, explore more corners, visit smaller structures, and enjoy the gardens and museums, plan to spend at least 3–4 hours — or even a full morning or afternoon.

Renting royal clothes

You can rent traditional Nguyen dynasty costumes inside the Imperial City, which makes for fun and unique photo opportunities. There are also rental shops in the city, possibly at a lower price, but renting onsite is more convenient and saves you from carrying the outfit around.

What to bring

Hue can be very hot in the summer, especially with all the walking involved. Make sure to bring plenty of water, sunscreen, and a hat. In the rainy season, pack an umbrella — many parts of the complex are open-air, and shelter is limited.

Facilities inside the citadel

Toilets and a small café selling drinks and snacks are available inside, but there are no full restaurants. Since you might be there for several hours, it’s smart to avoid visiting right around lunchtime or bring something small to eat later.

Guide or not?

The site is well laid out and easy to walk around, so you don’t need a guide to find your way. However, signage is limited, and many buildings have little explanation. If you want to understand the deeper context and stories, hiring a local guide — or using an audio guide — is a great choice.

Taking photos

Photography is allowed throughout most of the Imperial City. The only exception is in the ancestral temple dedicated to the Nguyen emperors, where signs clearly indicate that photos are not permitted.

Watching a traditional show

Inside the Royal Theatre, traditional music and performance shows are held up to three times a day. The show only starts if at least ten people attend, so it’s best to check the schedule early. It’s a nice way to cool off and enjoy a bit of royal-era culture.

Other historic sights in Hue

The Hue Imperial City is the heart of Vietnam’s last dynasty, but it’s far from the only reminder of royal life in the region. Over more than a century, the Nguyen emperors built temples, pagodas, and majestic tombs — many of them set in peaceful, scenic surroundings just outside the city. Each place reflects a different aspect of imperial tradition, from ancestor worship and spirituality to poetry, power, and personal legacy.

If you’re spending more time in Hue, these are some of the most impressive historic sites to add to your itinerary:

Thien Mu Pagoda

Thien Mu Pagoda is Hue’s most iconic religious site, perched on a hillside above the Perfume River. With its seven-story tower and tranquil gardens, this pagoda has long been a symbol of the city and a site of deep spiritual and political significance.

Tu Duc Tomb

Tu Duc Tomb is a romantic retreat turned royal mausoleum, built by Emperor Tu Duc as a peaceful escape and final resting place. Its pine-shaded grounds, lotus ponds, and poetic pavilions reflect the emperor’s literary soul and love of solitude.

Gia Long Tomb

Located deep in the countryside west of Hue, Gia Long Tomb is the oldest and most isolated of the Nguyen dynasty tombs. This vast, peaceful site offers panoramic views and a quiet atmosphere—ideal for travelers looking to explore beyond the main tourist circuit.

Minh Mang Tomb

Minh Mang Tomb is known for its perfect symmetry, ornamental bridges, and lotus-filled lakes. Designed to reflect the emperor’s Confucian worldview, the layout and architecture express order, discipline, and harmony with nature.

Khai Dinh Tomb

Khai Dinh Tomb stands out with its fusion of Vietnamese, Chinese, and European styles. The gray concrete exterior contrasts with a richly decorated interior, full of glass and porcelain mosaics. It’s one of Hue’s most distinctive—and photogenic—imperial sites.

Or explore our full list of highlights in this article: 10 Best Temples, Pagodas & Tombs in Hue