Who was Gia Long?

Gia Long, born Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in 1762, was a royal prince of the powerful Nguyễn family, which ruled southern Vietnam during a time when the country was divided between competing dynasties. In the late 18th century, a major uprising known as the Tây Sơn rebellion overthrew both the Nguyễn lords in the south and the Trịnh lords in the north, plunging the country into chaos. Nguyễn Phúc Ánh was the only surviving male of his ruling family after the Tây Sơn massacred most of his relatives in 1777, forcing him into exile at just 15 years old.

Over the next 25 years, he led a relentless military and political campaign to reclaim and reunify Vietnam. With support from local allies and some foreign assistance—most notably from French Catholic missionaries—he gradually regained control over the south, then launched campaigns against the Tây Sơn in central and northern Vietnam. In 1802, he declared himself emperor under the name Gia Long and established the Nguyễn dynasty, which would rule Vietnam until 1945. His reign marked the beginning of a unified Vietnamese state stretching from China to the Gulf of Siam.

What was the Nguyen Dynasty?

The Nguyễn dynasty was the last imperial dynasty of Vietnam, ruling from 1802 to 1945. It was founded by Gia Long after he unified the country following decades of civil war and internal division. Under the Nguyễn emperors, Vietnam became a centralized and bureaucratic state, with Confucianism as the guiding political and moral philosophy.

Although the dynasty initially stabilized and expanded the country, it eventually faced growing internal resistance and increasing pressure from European colonial powers. By the late 19th century, France had colonized Vietnam, though the Nguyễn emperors continued to rule in name until the monarchy was officially abolished in 1945. Understanding the Nguyễn dynasty provides important context for Gia Long’s legacy, as he laid the foundation for this entire period of Vietnamese history.

Key events in Gia Long’s life

Early life and Tây Son Rebellion (1762–1777)

Gia Long was born as Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in 1762 in Phú Xuân (modern-day Huế), into the powerful Nguyễn royal family that ruled southern Vietnam. At the time, Vietnam was split between the Nguyễn lords in the south and the Trịnh lords in the north, with the Lê emperors in Hanoi serving only as figureheads. This fragile balance collapsed when the Tây Sơn uprising erupted in 1771, led by three brothers from Bình Định Province.

In 1777, when Nguyễn Ánh was just 15 years old, the Tây Sơn forces captured and executed nearly his entire family. As the only surviving direct male heir of the Nguyễn clan, he suddenly became the unlikely leader of a collapsing regime. With no army, little support, and his life constantly at risk, he was forced to flee into hiding across the Mekong Delta.

Flight, Allies & First Battles (1777–1787)

After narrowly escaping death, Nguyễn Ánh was sheltered by Catholic priests in southern Vietnam and eventually made contact with the French missionary Pierre Pigneau de Behaine. The bishop saw potential in Nguyễn Ánh’s claim to the throne and began helping him gather international support.

During this period, Nguyễn Ánh experienced both early successes and devastating defeats. He retook Saigon in 1778 with the help of Cambodian allies and Chinese pirates, only to lose it again after ordering the assassination of his powerful general Đỗ Thanh Nhơn—an act that severely weakened his army. As Tây Sơn forces swept through the south, Nguyễn Ánh fled once more, spending time in Siam (modern-day Thailand) with his followers in exile.

The French Connection & Failed Treaty (1787–1789)

Facing repeated military failures, Nguyễn Ánh entrusted Pigneau with securing formal French support. In 1787, a treaty was signed in Versailles promising troops and military aid in exchange for trade privileges. However, the French Revolution was underway, and the promised official support never materialized.

Instead, Pigneau returned to Vietnam with a small group of volunteers and shipments of weapons. Although limited in number, these French soldiers played an important role in training Nguyễn Ánh’s forces and introducing European-style warfare. By 1789, he had regained a stronghold in Saigon, laying the groundwork for a larger comeback.

Consolidating the South (1789–1792)

With Saigon once again under his control, Nguyễn Ánh focused on strengthening his base rather than launching immediate offensives. This phase was defined by rebuilding his military infrastructure, thanks in part to his French advisors. He established a naval shipyard, constructed a massive European-style citadel in Saigon, and formed a professional army with improved artillery.

The region around Saigon, referred to as Gia Định, became his political and logistical stronghold. Administrative reforms were introduced, conscription systems were expanded, and military colonies were established to secure loyalty across ethnic groups. This gave Nguyễn Ánh the first real advantage he had held in years.

Turning the tide against Tây Son (1792–1801)

The death of Tây Sơn leader Nguyễn Huệ (Emperor Quang Trung) in 1792 created a power vacuum that Nguyễn Ánh was quick to exploit. He began a series of annual naval campaigns against the Tây Sơn heartlands, using the monsoon winds to his advantage. His modernized navy, supported by large European-style vessels, gained the upper hand in coastal battles.

Key victories followed, including the fortress at Quy Nhơn and the central provinces of Vietnam. Unlike earlier failed assaults, Nguyễn Ánh now had the manpower, ships, and supply lines to hold territory and push forward. Slowly but steadily, the Tây Sơn regime crumbled under pressure.

Unification and Coronation (1802)

By mid-1802, Nguyễn Ánh had captured both Huế and Hanoi. On June 1st, 1802, he crowned himself Emperor Gia Long—a name symbolically combining “Gia Định” (the south) and “Thăng Long” (the north, now Hanoi). For the first time in centuries, Vietnam was unified under a single ruler.

He requested official recognition from the Qing court in China, which was granted, though with a diplomatic twist: instead of naming the country “Nam Việt” as Gia Long had proposed, the Qing emperor reversed the characters and called it “Việt Nam.” Regardless, this marked the formal start of the Nguyễn dynasty.

Governance and Administration (1802–1820)

Once in power, Gia Long focused on stability. He reinstated Confucian ideals and implemented a new legal code, known as the Gia Long Code, modeled heavily on Qing Chinese law. He also revived the imperial examination system to select officials, aiming to rebuild a civil service class after decades of warfare.

To manage such a vast and newly unified territory, Gia Long divided Vietnam into three major zones—north, central, and south—allowing regional officials significant autonomy under his authority. While this approach helped maintain order, it also laid the groundwork for future decentralization conflicts.

Foreign Relations & Isolationism

Although Gia Long owed much of his military success to foreign support, he was cautious in his international dealings. He kept Cambodia under Vietnamese influence, stationing troops in Phnom Penh, and balanced diplomatic relations between Siam and Qing China.

He resisted European trade demands, rejecting offers from the British and Dutch and limiting France’s influence despite his earlier connections. While French advisors remained at court, Gia Long preferred isolation over deeper commercial or political ties with the West.

Infrastructure and Social Policies

Gia Long invested heavily in building and rebuilding Vietnam’s infrastructure. He oversaw the construction of roads, canals, and postal networks that connected the north and south. He also launched a national fortification campaign, commissioning more than a dozen stone citadels across the country in both European and Chinese styles.

His social reforms promoted Confucian education while sidelining Buddhism and expressing unease toward Catholicism, despite having tolerated missionaries during his rise. He reinstated the National Academy in Huế and placed emphasis on loyalty to the monarchy and traditional family values.

Death and Succession (1820)

Gia Long died on February 3, 1820, after nearly two decades as emperor. He was buried at the Thiên Thọ Tomb near Huế, beginning the imperial tomb complex of the Nguyễn emperors. Though his eldest son had died during the Tây Sơn wars, Gia Long bypassed his Catholic grandson and named his more traditionalist son Nguyễn Phúc Đảm as successor—later known as Emperor Minh Mạng.

His legacy is complex: a skilled unifier and founder of Vietnam’s final dynasty, but also a ruler who favored central control, strict orthodoxy, and political isolation over modernization.

Emperor Gia Long in Vietnam today

Though Gia Long passed away over 200 years ago, his legacy still lives on across Vietnam. From imperial tombs and fortresses to school names and museum displays, the imprint of Vietnam’s first Nguyễn emperor can still be seen—and debated—throughout the country.

1. Tomb of Gia Long (Thiên Tho Tomb)

Gia Long’s final resting place is located deep in the countryside, about 16 km south of Hue, far more secluded than the later tombs of his descendants. Known as Thiên Thọ Tomb, it is part of a vast complex spread across pine-covered hills with multiple temples, altars, and lakes.

Unlike the more ornate royal tombs that followed, Gia Long’s tomb is understated and often quiet, with few tourists. Reaching the site requires private transport (car or motorbike), and the road is narrow and unmarked in parts, so a guide or local driver is helpful. The setting is peaceful and scenic, but facilities are minimal—this is more a place of reflection than sightseeing.

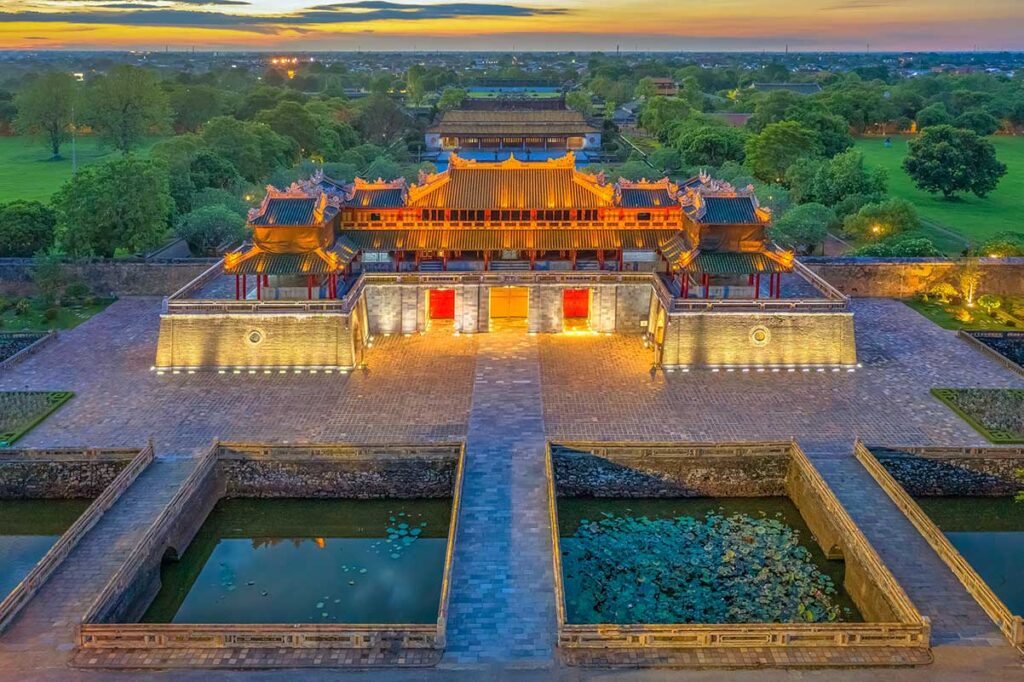

2. Gia Long and the Imperial City of Hue

Gia Long was the architect behind Hue’s transformation into Vietnam’s imperial capital. After declaring himself emperor, he moved the seat of government to Hue and began construction of the Imperial City (Đại Nội), modeled after Beijing’s Forbidden City but adapted with Vietnamese and French military elements.

While much of the structure was expanded and completed by his son Minh Mạng, the original layout, moat system, and stone citadel walls date to Gia Long’s reign. Visitors to the Hue Citadel today are walking through the strategic vision of Gia Long—where traditional Asian palace design meets early modern military planning.

3. Museum exhibits related to Gia Long

Artifacts and documents related to Gia Long can be found in several museums, though there is no dedicated Gia Long museum. The Hue Museum of Royal Antiquities (just outside the Imperial City) houses items from the early Nguyễn era, including royal garments, furniture, and architectural details from his time.

In Hanoi, the Vietnam National Museum of History also includes exhibits about the Nguyễn dynasty and Gia Long’s unification of Vietnam, though the focus is more general. Most references to Gia Long appear within broader displays about the Nguyễn dynasty or Vietnam’s imperial history, rather than as standalone sections.

4. Streets, Schools & Places Named After Him

Several streets, especially in southern Vietnam, are named after Gia Long, though many were renamed after 1975. In Ho Chi Minh City, for example, Gia Long Street became Lý Tự Trọng Street, reflecting post-war shifts in historical narratives.

A few schools and temples in Hue and the Mekong Delta still bear his name or honor him in ancestral halls. However, unlike figures such as Hồ Chí Minh or Quang Trung, Gia Long’s name is not widely used in public naming today—likely due to his perceived conservatism and association with monarchy.

5. Gia Long in modern historical narratives

Gia Long’s legacy in Vietnam today is complex. On one hand, he is recognized as the man who unified the country and laid the foundations for modern Vietnam. On the other, critics view him as overly conservative, too reliant on foreign assistance, and responsible for reversing progressive Tây Sơn reforms.

In Vietnamese textbooks, he is generally presented in a neutral or slightly positive light—emphasizing his unification of Vietnam, administrative reorganization, and resistance to Western influence. However, his harsh suppression of rivals and traditionalist policies are also noted. Among historians, debates continue about whether he was a national savior or a missed opportunity for reform.

Other emperors of Vietnam

Vietnam had many emperors across multiple dynasties, each shaping the country in different ways. Gia Long was one of the most pivotal figures—unifying the nation and founding the Nguyễn dynasty—but he was far from the only important ruler in Vietnamese history.

- Lý Thái Tổ (1009–1028): Moved the capital to Thăng Long (modern-day Hanoi) and established the Lý Dynasty, marking a new era of Vietnamese independence and cultural identity.

- Trần Nhân Tông (1279–1293): Successfully defended Vietnam against Mongol invasions, then abdicated the throne to become a Buddhist monk and spiritual leader.

- Lê Thánh Tông (1460–1497): Presided over a golden age of Confucian scholarship, law, and territorial expansion; known for his effective, centralized administration.

- Quang Trung (Nguyễn Huệ) (1788–1792): A revolutionary Tây Sơn general who defeated the Qing army and tried to modernize Vietnam before dying unexpectedly at the peak of his power.

- Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Gia Long’s son and chosen successor, known for his strict Confucianism, rejection of Catholic influence, and the centralization of imperial control.