History & Origins of the Japanese Bridge

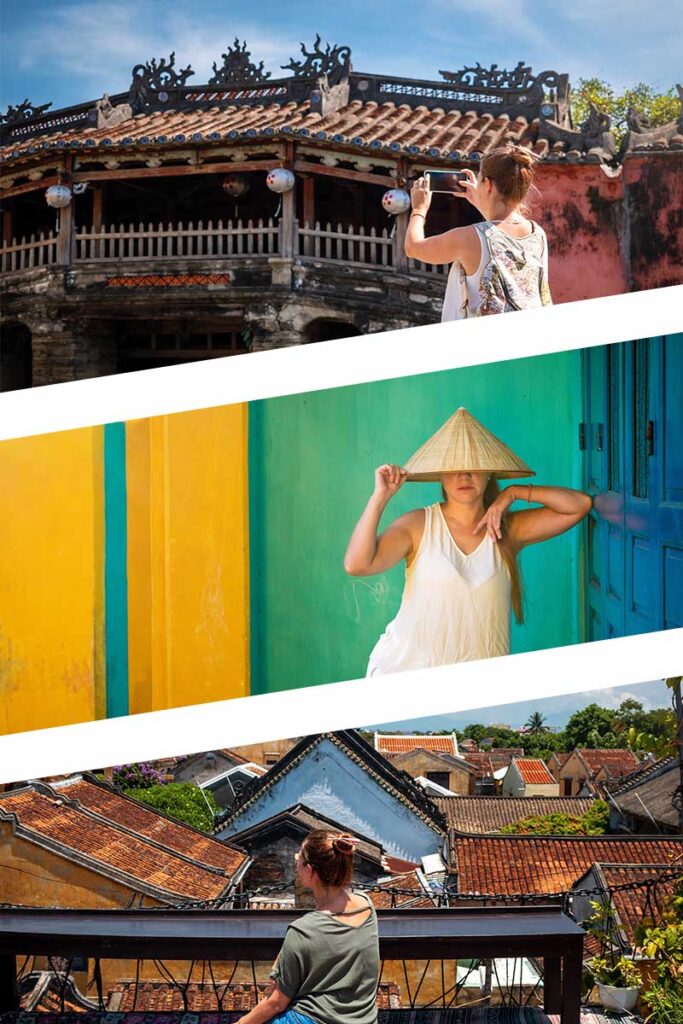

The Japanese Bridge was built in the late 16th century by Japanese merchants living in Hoi An, who constructed it to link their neighborhood with the Chinese quarter across a small canal. More than just a practical crossing, it became a symbol of peace and cultural unity between these once-distinct communities.

Local legend ties the bridge to Namazu, a mythical earthquake-causing sea monster. According to the story, the bridge was built to pin down the monster’s back — a way to protect Vietnam, Japan, and India from natural disasters.

In 1719, during a visit to Hoi An, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Chu gave the bridge the poetic name Lai Viễn Kiều, meaning “Bridge for Welcoming Guests from Afar.” Despite changes in Hoi An’s economy and the decline of its port, the bridge remained a powerful symbol of the city’s trading past. In 1990, it was officially designated a National Historic-Cultural Relic of Vietnam.

Architecture & design

The Japanese Bridge is a covered wooden footbridge with a gently curved tiled roof and a small pagoda built into its center. It stretches about 18 meters across a narrow canal, part of the Thu Bon River system, and connects Tran Phu Street (the former Chinese quarter) with Nguyen Thi Minh Khai Street (the old Japanese area).

What makes this bridge unique is its blend of architectural influences. While originally built by the Japanese, the structure also reflects Chinese and Vietnamese styles added through later renovations.

You’ll see curved wooden beams, yin-yang roof tiles, and carved inscriptions in Chữ Hán (classical Chinese characters).

At each end of the bridge are statues of a dog and a monkey — symbols of protection. According to local belief, construction started in the year of the monkey and finished in the year of the dog, which may explain their placement. Others say the animals were chosen to guard the bridge spiritually. Either way, they’ve become an iconic part of its identity.

The temple inside the Bridge

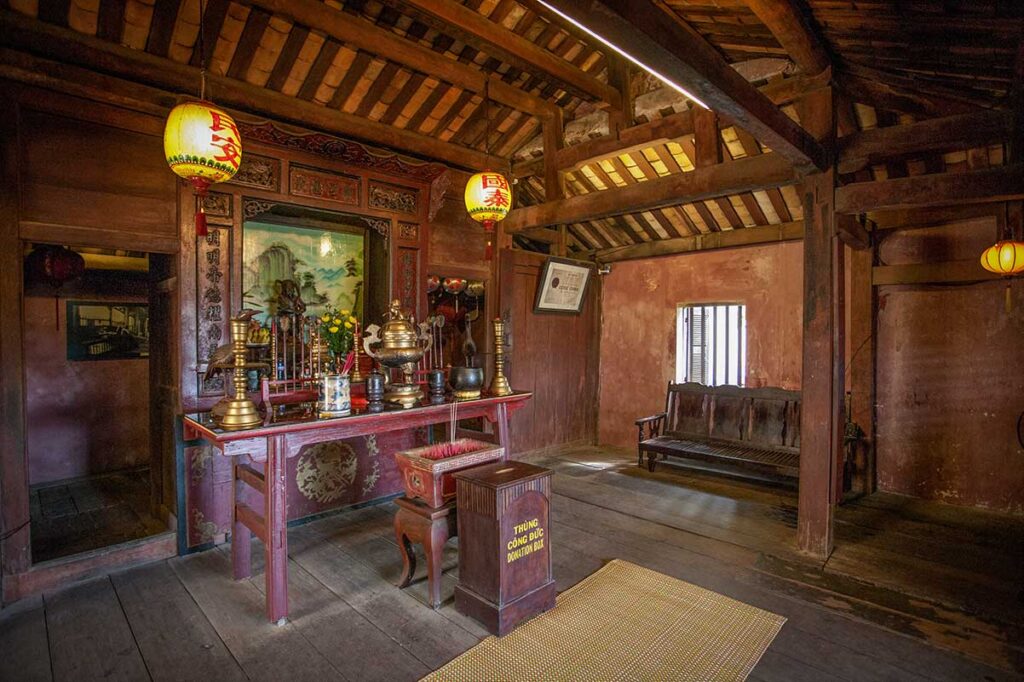

The Japanese Bridge is officially named Chùa Cầu, meaning “Pagoda Bridge,” this structure is more than just a crossing — it’s also a place of worship.

Inside the covered section, you’ll find a small temple dedicated not to Buddha, but to Trấn Võ Bắc Đế (the Northern God of Prosperity, Protection, and Health).

Locals still come here to make offerings and prayers, especially for good fortune and well-being. The temple isn’t large or elaborate, but it adds meaningful depth to the bridge — blending architecture with spirituality in a way that reflects Hoi An’s unique cultural mix.

Renovation & preservation

Over its long history, the Japanese Bridge has undergone several renovations to protect its wooden structure from wear, weather, and floods. Major restoration efforts took place in 1817, 1917, 1986, and again starting in 2020, when concerns about erosion and structural weakening prompted renewed preservation work.

These repairs focused on stabilizing the foundation, reinforcing the roof, and preserving the decorative and architectural details. Given its age and cultural value, the bridge is carefully maintained to retain its original appearance while ensuring it remains safe for visitors.

As of now, there are no active renovations, and the bridge is fully open for public access.

How to visit the Japanese Bridge

The Japanese Bridge sits at the western end of Hoi An Ancient Town, connecting Nguyen Thi Minh Khai Street (formerly the Japanese quarter) with Tran Phu Street (once the Chinese quarter). It’s easily reachable on foot as part of a self-guided stroll through the Old Town.

There is no entrance fee to cross the bridge, though a Hoi An Ancient Town ticket is required to enter certain historic buildings nearby.

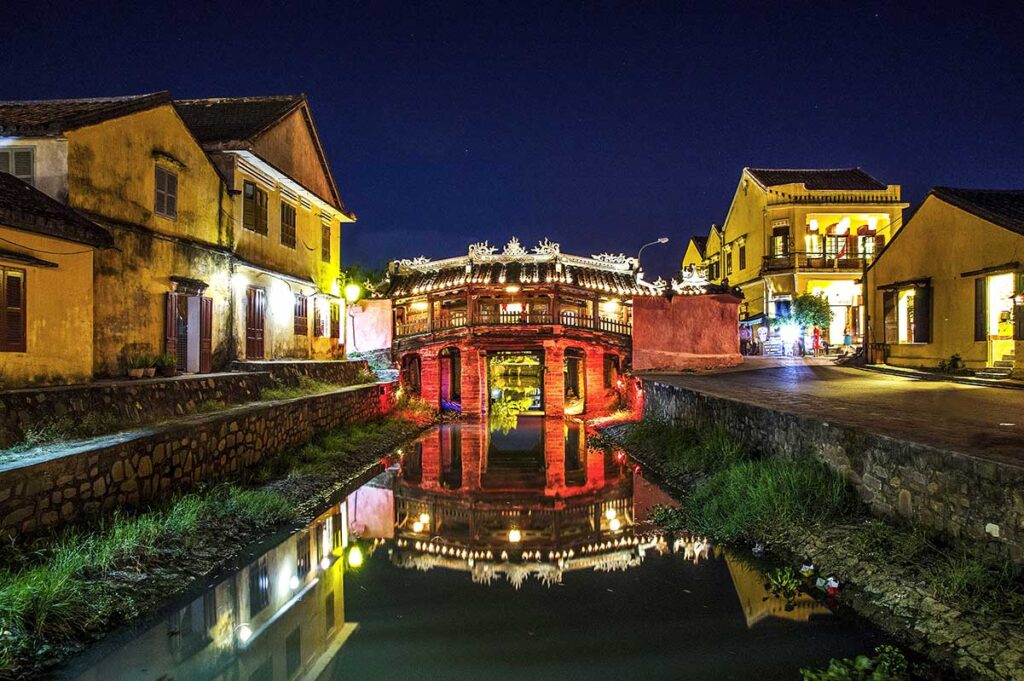

To avoid crowds, the early morning is ideal for quiet photos. For atmosphere, visit in the evening, when the bridge is softly illuminated and surrounded by the colorful glow of Hoi An’s lanterns.

Interesting facts

It’s featured on Vietnamese currency

The Japanese Bridge is such a national symbol that it appears on the back of Vietnam’s blue 20,000 VND banknote. It reflects not just the bridge’s cultural value to Hoi An, but its importance to Vietnamese heritage as a whole.

It’s both a bridge and a temple

The structure isn’t just for crossing — it also houses a small temple in the center. In Vietnamese, it’s called Chùa Cầu, literally meaning “Pagoda Bridge.” The bridge spans a canal while the temple adds a spiritual layer that’s still relevant today.

The temple doesn’t worship Buddha

Unusually for Vietnam, the temple honors Trấn Võ Bắc Đế, the northern deity of prosperity and protection — not Buddha. Locals still stop here to light incense and pray for good fortune and health.

The statues represent time and protection

At one end of the bridge is a monkey, at the other a dog — said to symbolize the years when construction began (Year of the Monkey) and ended (Year of the Dog). In Japanese culture, these animals also represent guardianship.

It was once open to motorbikes

During the French colonial period, the bridge was modified to accommodate vehicles. In the 1980s, it was restored to pedestrian-only access to better protect the aging structure.

Practical visiting tips

Make it part of your Old Town walk

The Japanese Bridge is at the western end of Hoi An Ancient Town, near Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai Street. You don’t need a special trip — it’s naturally part of walking routes through the historic center. Combine it with nearby sights like Tan Ky House, Phuc Kien Assembly Hall, and Hoi An Market.

Hoi An Walking Tour by Local Guide

- Experience Explore Hoi An’s Ancient Town with an expert local guide and insider stories.

- Includes Market visit, traditional house, colorful temples, and coffee break by electric car.

Visit early for peace, or late for lights

From 10:00 AM onwards, the bridge gets crowded with tour groups and photo seekers. For a quieter visit and better photos, try going before 9:00 AM.

After dark, the bridge is beautifully lit with lanterns and becomes part of the vibrant night-time atmosphere of Hoi An. Expect more people, but also more charm.

Best photo spot is on the opposit bridge

For a clear, front-on view with the bridge and its reflection, cross the small footbridge opposite. This angle is ideal at golden hour or after dark when the lanterns glow.

No ticket needed — it’s free

Some attractions in Hoi An require a heritage ticket, but the Japanese Bridge is free to cross. There are no guards or restrictions unless maintenance is underway.

You don’t need a guide — but context helps

Most people just walk across and take a quick photo. But reading up beforehand (like this guide) gives you the background to appreciate what you’re seeing — from architectural details to its layered symbolism.

Is the Japanese Bridge worth visiting?

Yes — it’s one of the most iconic and culturally important spots in Hoi An.

It doesn’t take long to visit, but it’s free, photogenic, and rich in history.

The bridge is ideal for a short pause during your Old Town walk — a place to reflect, take a few photos, and appreciate the town’s multicultural heritage.

Just keep expectations realistic: it’s a small structure that gets crowded during the day, but it’s still well worth seeing — especially if you value history and symbolism.